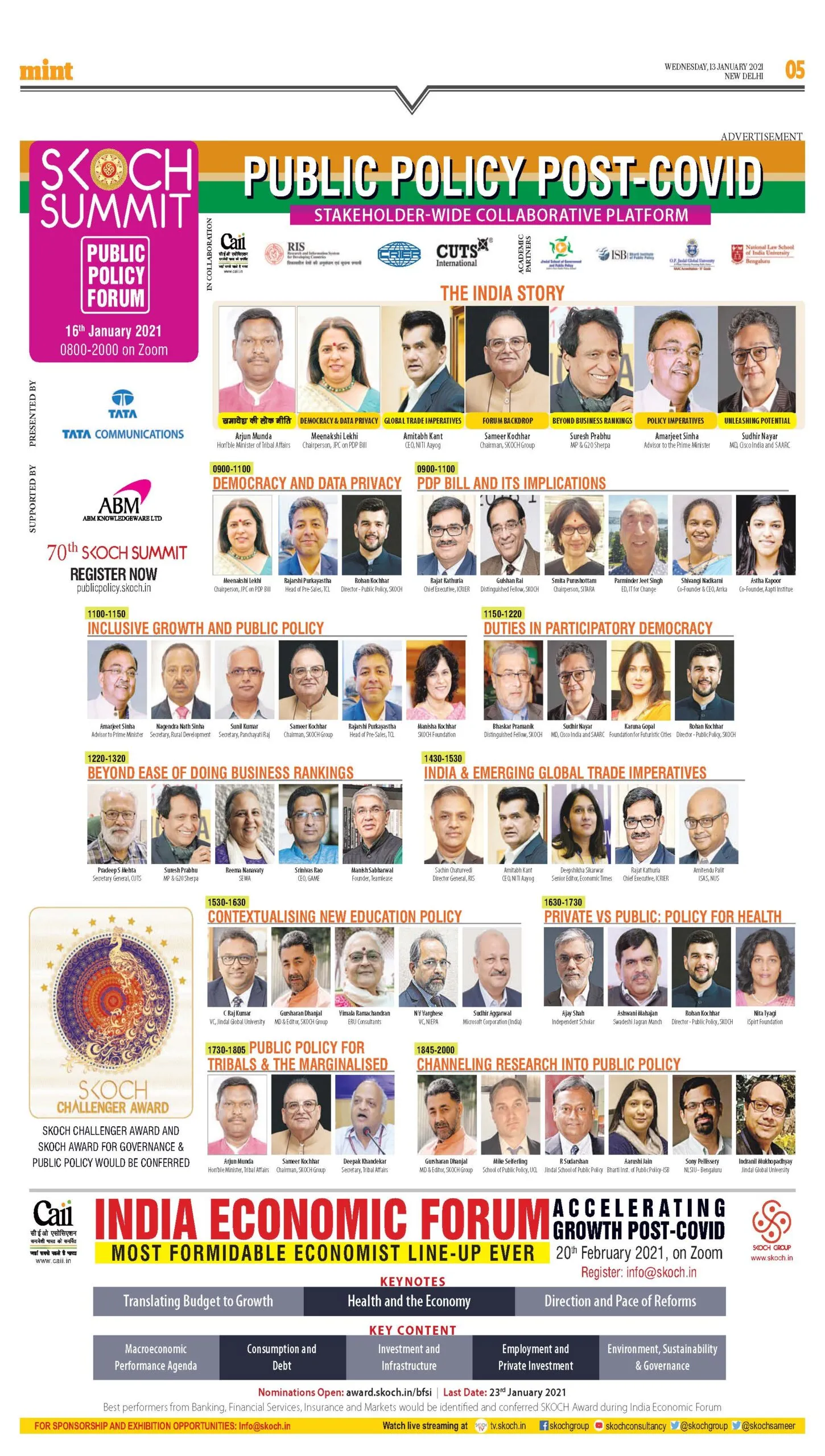

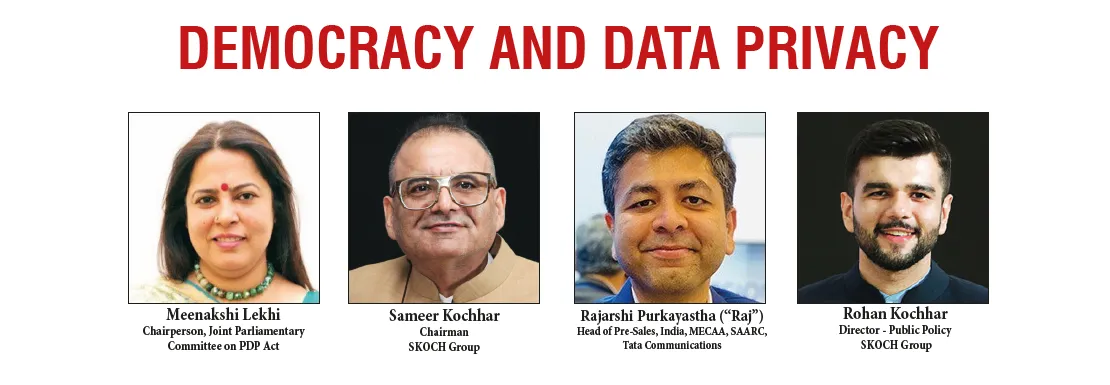

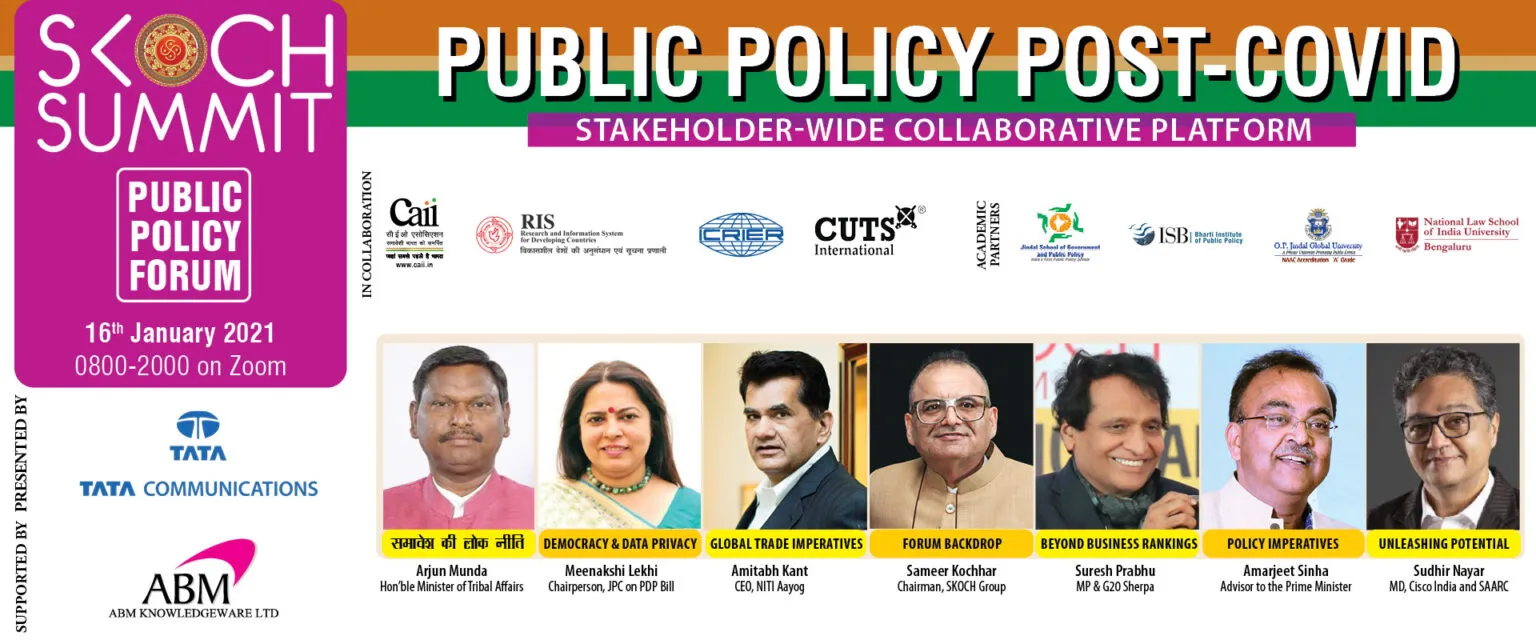

Public Policy Forum & LITFest 2021:

Public Policy Post COVID

0800-2000 hrs | 16 January 2021

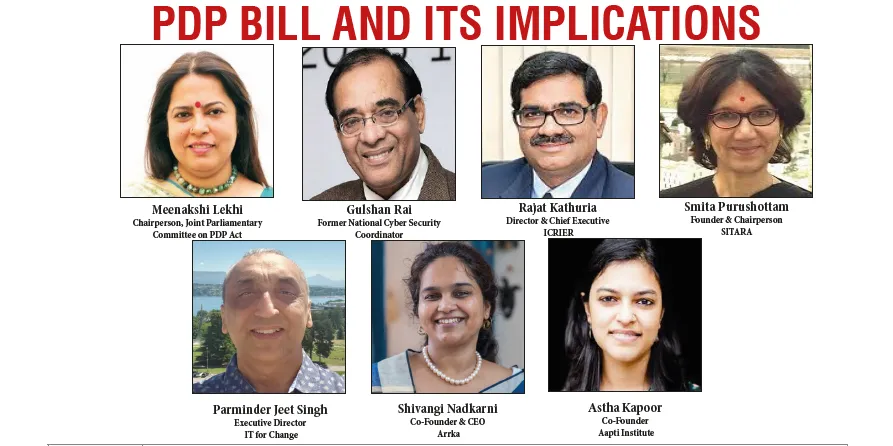

PDP BILL AND ITS IMPLICATIONS

‘Data’ has emerged as the essence of most modern-day economies. In this era of big data many firms derive their value from exclusive data access and other intangible assets, as opposed to machinery and other physical assets. The innate characteristics of ‘data’ raise several policy questions related to its value, ownership, regulation and sovereignty. Often to achieve national objectives, conflicts get created and need resolution-in the data space the potential policy conflicts are just more profound. Consequently, only a few countries have enacted data protection regulations while others have started the process. The Indian Government constituted a Data Protection Committee (DPC) in 2017 which proposed a comprehensive law on data protection. The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 was introduced in the Parliament on 11 December 2019 and the proposed legislation is currently being analysed by a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC). The proposed legislation seeks to provide for the protection of personal data of individuals and proposes a framework for processing of such data by other entities. The overarching goal of this discussion would be to highlight the effectiveness of the proposed legislation in striking a balance between protecting a nascent but fast-growing digital economy in India and the rights of over a billion users.

The panel discussion will deliberate the following questions:

- What are the implementation gaps and challenges in the proposed Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 including institutionalising and functioning of the Data Protection Authority (DPA)?

- What will be the economic implications of the proposed legislation? How would the compliance requirements impact firms in the long and short run? Will the legislation impact India’s trade competitiveness, especially in the services sector?

- Has privacy emerged as an important form of non-price competition? Do existing/ proposed legislations allow for institutional collaborations to assess and regulate this aspect of privacy? If not, is this necessary?

Beyond Ease of Doing Business Rankings

The Government of India has wholeheartedly adopted the World Bank’s approach to rank countries on its Ease of Doing Business indicators. It has aimed improvements on rankings with a single-minded pursuit. The Government has even launched the Business Reform Action Plan to rank states on business reforms they claim to have implemented, and promoted competitive federalism.

Despite benefits and shortcomings of rankings, it is becoming evident that climbing charts cannot become an end in itself and much more efforts are required on the ground to make life easier for entrepreneurs, both small and large, each facing their unique sets of challenges.

These challenges can be broadly categorised into stock and flow of regulatory requirements. The former relates to existing requirements, and their implementation and the latter with the manner in which such requirements are changed.

Subjecting the existing requirements to a three-step test of legality, necessity and proportionality, and the proposals to a cost-benefit analysis would be necessary to address such challenges. This will require institutionalising reforms such as regulatory impact assessment. The panel discusses the following:

- Is the government right in spending and capacity on ease of doing business rankings or such rankings should be discarded in favour of other result-oriented measures?

- What reforms should government adopt to take its ease of doing business efforts to the next level and is there something we can learn from other successful countries?

- How to overcome bureaucratic preference to status-quoism and apathy to change and what incentives are needed to ensure effective adoption and implementation of such new sets of reforms?

India & Emerging Global Trade Imperatives

In the post-COVID world, with key economies raising barriers to international trade it could seem that the era of large regional trade agreements are over. Two contradictory events recently; the first was that ASEAN+5 made operational the Regional Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement. India as it decided in 2019, stayed away. the other is UK walked away from what was essentially a regional trading agreement—the European Union as Brexit. Meanwhile a new US administration takes over, which is far less hostile to the idea of trade agreements.

The world is divided between the need for ensuring safety in their supply networks and so bringing manufacturing closer home, yet realising that growth is only possible to give a fillip to with deeper trade networks. The panel discusses the following:

- Will this then move the needle away from regional trading blocs to bilateral free trade agreements?

- Will countries like India and UK be more keen to enter such agreements?

- What then happens to the 18 odd 18 regional trade agreements India is a signatory to?

Contextualising New Education Policy

India has recently come up with its New Education Policy (NEP). Given the history of policymaking for the education sector in India, since independence, this is the fourth document to have been introduced by the government, the last one being developed in 1992. The promulgation of the new policy raises a fundamental question about the need of having a new policy. One may also ask how new the latest policy document is compared to its predecessors. The Panel Discussion aims at contextualising the policy vis-à-vis the ground level reality. It discusses the following:

- What perceptible changes are observed in the recent policy document in terms of objectives, intent and operational details compared to the earlier ones?

- What were the felt-needs of introducing the new policy?

- How well does this policy document capture in a seamless way the interactions among primary, secondary and higher education systems?

- How to take care of the resource constraints that may come in the way of achieving the policy objectives?

Private vs Public: Policy Direction for Public Health

Health policy is a tough call. Thinking about market failure and state capacity from first principles is required in public health and in healthcare. There are market failures in public goods and externalities that essentially constitute ‘public health’. Equally, there are market failures in asymmetric information and market power that shape healthcare. The debate then is whether we need more state or less in public health and healthcare. There is a lot of interest in technological fixes, all the way from National Digital Health Blueprint to Artificial Intelligence to replace doctors. This panel tries to put the role of state, private sector and digital technologies in context such that India may finally get a winning policy prescription for health that is widely acceptable.

Channeling Research into Public Policy

This panel focuses on the role that research institutions, academia, and Universities can play in times when reactions to public policy and governance challenges are increasingly becoming polarised along political lines, mainstream media is largely seen to be biased, and effective and deep research and analysis into questions of public policy is lacking. It focuses largely on four themes:

- In light of the quivering pillars of the fourth estate, is the onus of creating an informed civil society on academia?

- How do we make specialised academic research more mainstream and help create informed debate in light of recent global events?

- How should academia break free from the echo chamber of academic journals?

- What is the role that students and policy professionals could play in catalysing this change?